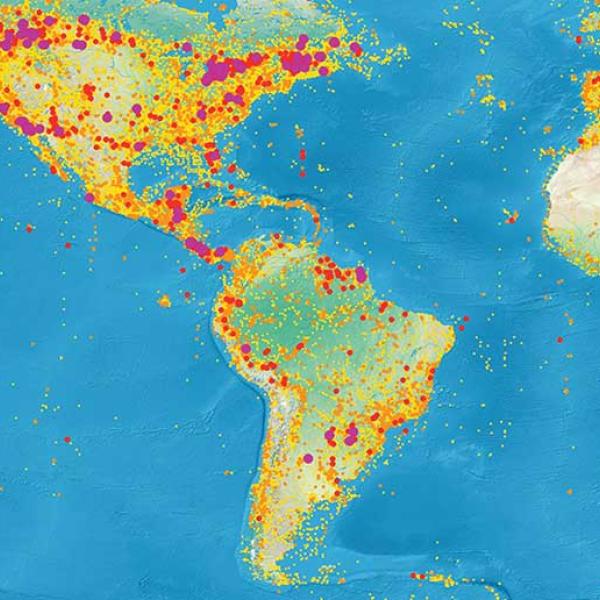

The stress on our freshwater resources has reached an unfathomable magnitude as the biodiversity of our lakes and rivers has declined by more than 80 percent worldwide over the past 40 years. Given the accelerating impacts of climate change and invasive species on aquatic systems, the need to improve freshwater monitoring has become urgent, says Stephen Lougheed, who holds the Baillie Family Chair in Conservation Biology at Queen’s University. With one-fifth of the planet’s freshwater reserves, Canada has a natural interest and global responsibility to protect this precious resource, but its strategy so far is inadequate, he says.

A new conservation research centre, supported through the CFI’s Innovation Fund, will help close that gap. Led by Lougheed, the Environmental and Climate Change Observatory of Ontario (ECCO-Ontario) will assess aquatic biodiversity in Eastern Ontario, including the highly affected Upper St. Lawrence River. It will include climate stations and drones for monitoring environmental change in real time, specialized microscopes to measure the response of observable traits in cells and whole organisms to varied environmental stressors, and molecular biology labs to better understand the genetic basis of adaptation in aquatic species.

An interdisciplinary research initiative, ECCO-Ontario aims to inform Canada’s efforts to attain United Nations Sustainable Development Goals on clean water and climate action.

New funding will also support an Indigenous Knowledge Centre, which will provide a space where Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers and Western scientists can meet to plan and discuss research and develop recommendations for managing aquatic environments sustainably.

Indigenous Knowledge of ecology and land and water stewardship practices are essential to advancing conservation research, says Lougheed. “Indigenous communities have a deep land-based knowledge that we have to embrace for stewardship and if we are to have any possibility of success at addressing environmental challenges,” he says.

At the heart of ECCO-Ontario is a research partnership with the River Institute in Cornwall, Ont., the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne Environment Program, and the First Nations Technical Institute in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, among other institutions. Indigenous and non-Indigenous partners will work together to survey, for example, historical changes in Ontario ecosystems and probe the impacts of stressors such as increased human population, intensive agriculture and pollutants on lake and river systems.

“The goal of building deeper and more meaningful relationships with local Indigenous communities,” says Lougheed, “will be a really important legacy of this project.”

Return to the collection called “The power to transform”