Trevor Lucas, ashore here in Inuvik, Northwest Territories, has made nine voyages through Canadian Arctic waters as a Marine Wildlife Observer aboard the Canadian research icebreaker CCGS Amundsen. His notes and photos of bowheads and belugas, of seals and polar bears and birds, are part of a wide range of activities carried out annually on the Amundsen, among the best equipped research vessels in the world.

Photo: Keith Levesque/ArcticNet

The Amundsen is shown here on duty in the Beaufort Sea, in the western Arctic. The decks are loaded with supplies and equipment for a months-long voyage. The 98-metre vessel began life in 1979 as the Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker Sir John Franklin. It was re-launched in 2003 as the research ship Amundsen by a consortium of Canadian universities, research centres and the Canadian government following a major retrofit financed by the CFI. Among its new features: a moon pool, a hole right through the bottom of the ship that allows underwater access in rough or iced-over seas.

Photo: Martin Fortier/ArcticNet

A long-tailed jaeger hovers near its nesting site on Bylot Island, Nunavut. The long-tail nests on Arctic tundra in summertime, and spends winters at sea in the southern hemisphere. It subsists largely by bullying food away from smaller birds.

Photo: Andréanne Beardsell/ArcticNet

The Amundsen moored off Salluit, a community of about 1,400 on the northern coast of Québec's Ungava Peninsula. A Hudson’s Bay Company post occupied the townsite in the 1930s. Later there were missions, a school, and from 1959, permanent residences.

Photo: Isabelle Dubois/ArcticNet

Edith Hogak and James Kuptana of Sachs Harbour, here poring over regional maps, are among the Inuit who have shared their knowledge of the land with ArcticNet researchers. ArcticNet is a network that brings together Canadian scientists, Inuit organizations, northern communities, federal and provincial agencies, and the private sector to study the effects of climate change and modernization of the coastal Canadian Arctic. Its year-round home is at Université Laval in Quebec City. In summer, it’s on board the Amundsen.

Photo: Doug Barber/ArcticNet

Researchers undertake the challenging task of setting nets for arctic cod under the ice of the Beaufort Sea, as the Amundsen idles nearby. The work carried out was part of a year-long study of the “flaw lead” off Banks Island. A flaw occurs when sea ice drifts away from landfast ice — the resulting open water is a flaw lead. Such leads routinely stay open through winter, harbouring unusually rich sea life and offering insights into the effects of climate change.

Photo: Doug Barber/ArcticNet

A well-bundled researcher works in a wonder-world that few others will ever witness: under the Arctic ice.

Photo: Jeremy Stewart/CFL

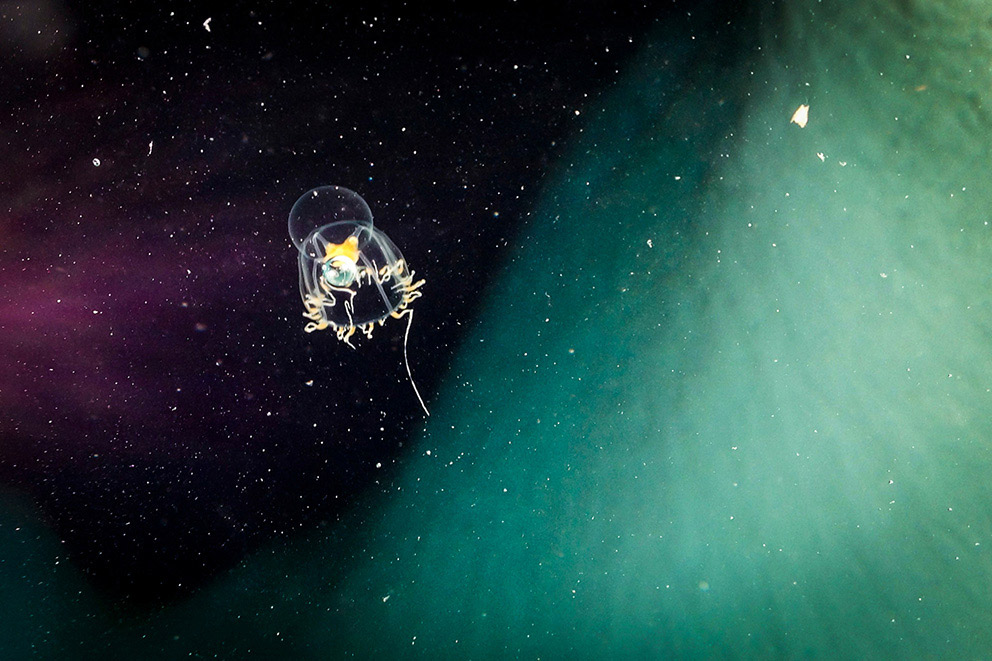

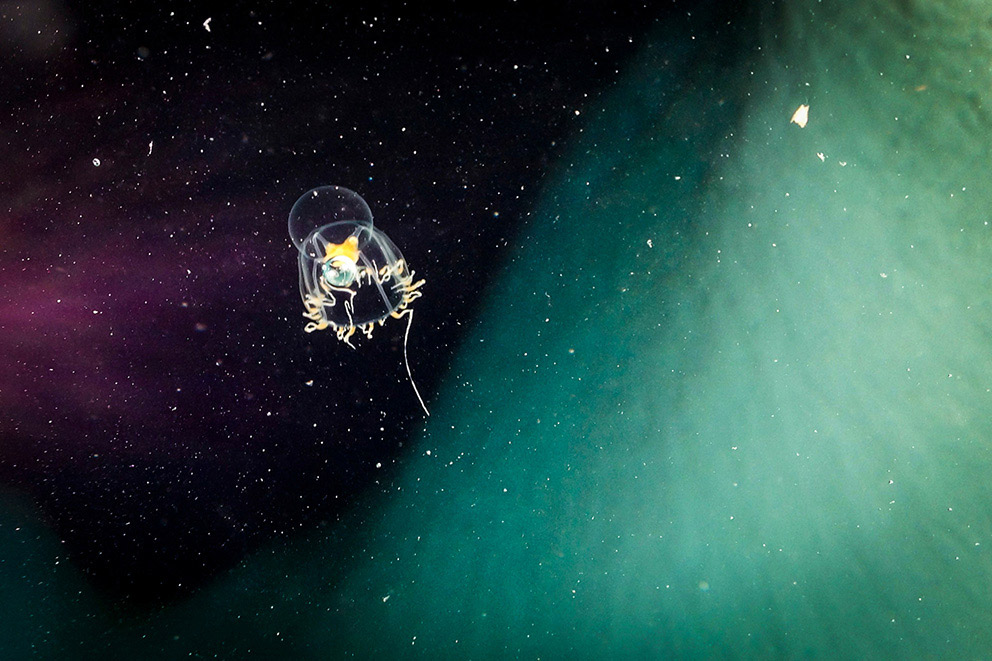

Not a denizen of deep space, but a jellyfish that came to say hello. Leuckartiara octona lives in oceans around the world, including here, in the frigid waters off Victoria Island, in the western Canadian Arctic.

Photo: Anne-Lise Ducluzeau/ArcticNet

ArcticNet scientists depart the Amundsen to sample surface waters around a drifting iceberg in northern Baffin Bay, between Ellesmere Island and Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland). Craft aboard the Amundsen include a landing barge, two Zodiacs, lifeboats and a Bell 429 helicopter. The Amundsen itself, of course, is named for the spectacularly successful Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen (1872-1928), first to sail the Northwest Passage, first to reach the South Pole, perhaps first to reach the North Pole, too.

Photo: Martin Fortier/ArcticNet

ArcticNet scientists seen sampling meltwater again, this time from a vast glacier approaching Makinson Inlet, Ellesmere Island.

Photo: Martin Fortier/ArcticNet

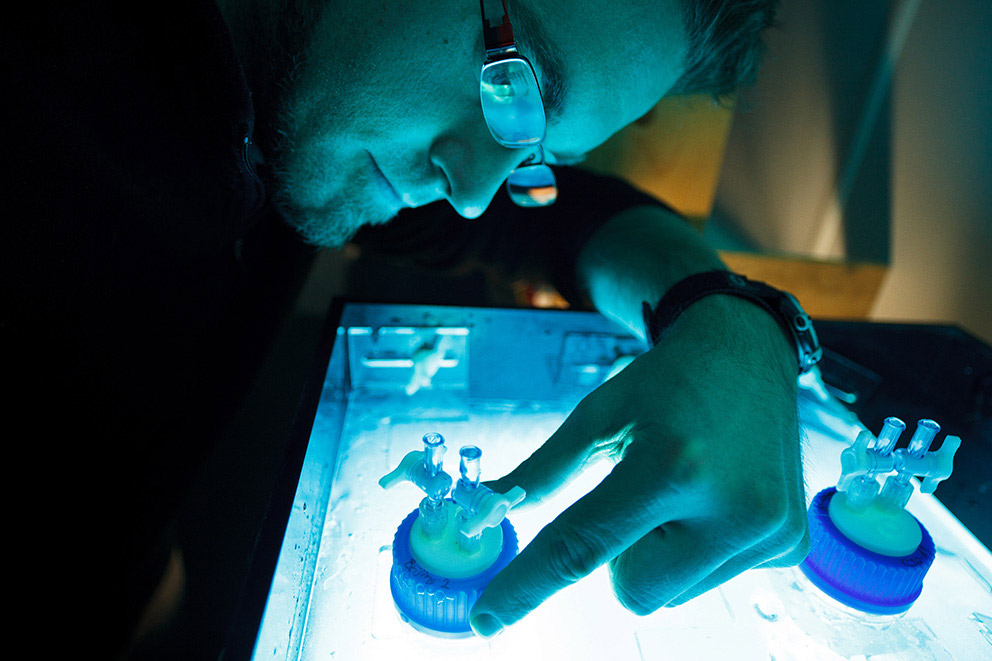

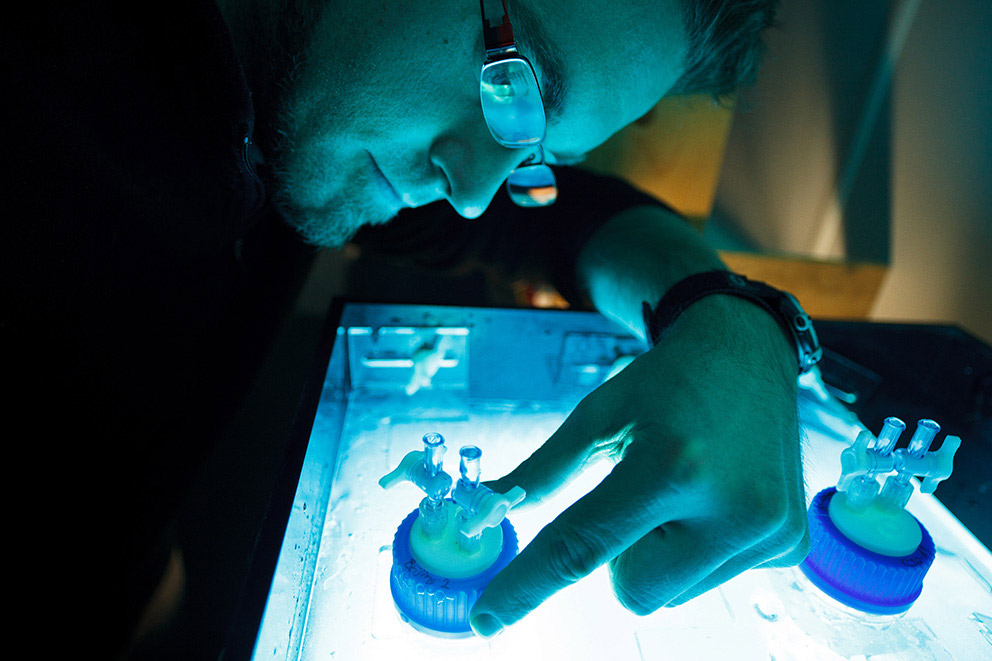

Scientist Jonathan Gagnon manipulates incubation bottles containing samples of phytoplankton plucked from Arctic waters, in one of 22 laboratories on board the Amundsen. On its regular summertime Arctic expeditions, the Amundsen accommodates a sizeable seaborne stable of scientists.

Photo: Ariel Estulin/ArcticNet

Aboard the Amundsen, nurse François de Courval discusses clinical research results with Inuit Health Survey participant Delilah Manik. The Amundsen has played a vital role in a comprehensive multi-year, 36-community Inuit health assessment, serving as survey headquarters, testing clinic and floating hospital. The results of the survey could help improve health care planning, personal health and community wellness for Inuit.

Photo: Stephanie McDonald

The Amundsen in Gibbs Fjord, on the north shore of Baffin Island, dwarfed by mountains of monumental scale and, in the foreground, a great glacier. “The Arctic is another world, another dimension,” says Keith Lévesque, ArcticNet's Marine Research Manager and a veteran northern scientist. “You never get tired of it, you’re continually amazed by what we have here in Canada. I wish more people could see it. They’d feel passionate about it, too.”

Photo: Martin Fortier/ArcticNet