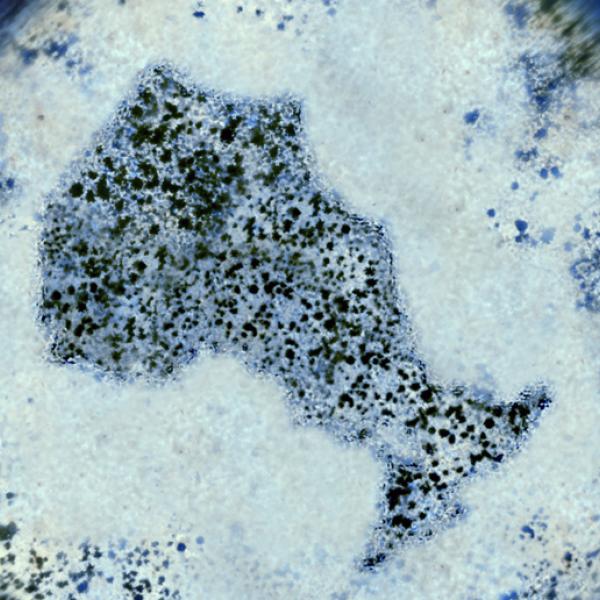

Last August, the local health unit in North Bay, Ont., warned that another harmful algae bloom had formed in Lake Nipissing’s Callander Bay, a popular recreational area at the east end of the lake. For many in the affected area, that meant keeping the taps turned off and thinking twice before eating the walleye they caught that morning.

“Lake Nipissing contributes an estimated $100 million each year to Ontario’s economy.”

The algae produces a toxin that can contaminate drinking water and build up in the organs and flesh of fish, making them unsafe to eat. But the bacterial scum is more than a health concern — especially for the many local businesses that depend on the lake. “There are certain areas that I avoid completely,” says Regan Thompson, a professional fishing guide and owner of Lake Nipissing’s Mashkinonje Lodge. “It definitely impacts the bottom line.”

Those impacts add up. Home to the Nipissing First Nation fishery and a popular destination for boaters, cottagers and recreational anglers, Lake Nipissing contributes an estimated $100 million each year to Ontario’s economy.

Algae blooms have been on the rise in the region for more than 20 years as a result of runoff of excess fertilizer from agricultural land as well as warmer air and water temperatures, among other things. To better understand the conditions that lead to algae blooms on Lake Nipissing, researchers from Nipissing University are employing CFI-funded sensors and data buoys to glean valuable insights into how and why they form. The monitoring stations have been taking measurements every five minutes for nearly five years, producing a mountain of data on water temperature, weather conditions, phosphorus levels and other factors that could be contributing to fostering the blooms. This will provide critical insight for more effectively managing them.

“No one likes having algae blooms,” says Thompson. “If there’s something that we could do to control it and maybe even get rid of it, it would be huge.”

Photo credit: Captured Seconds - Adam Dudzinski