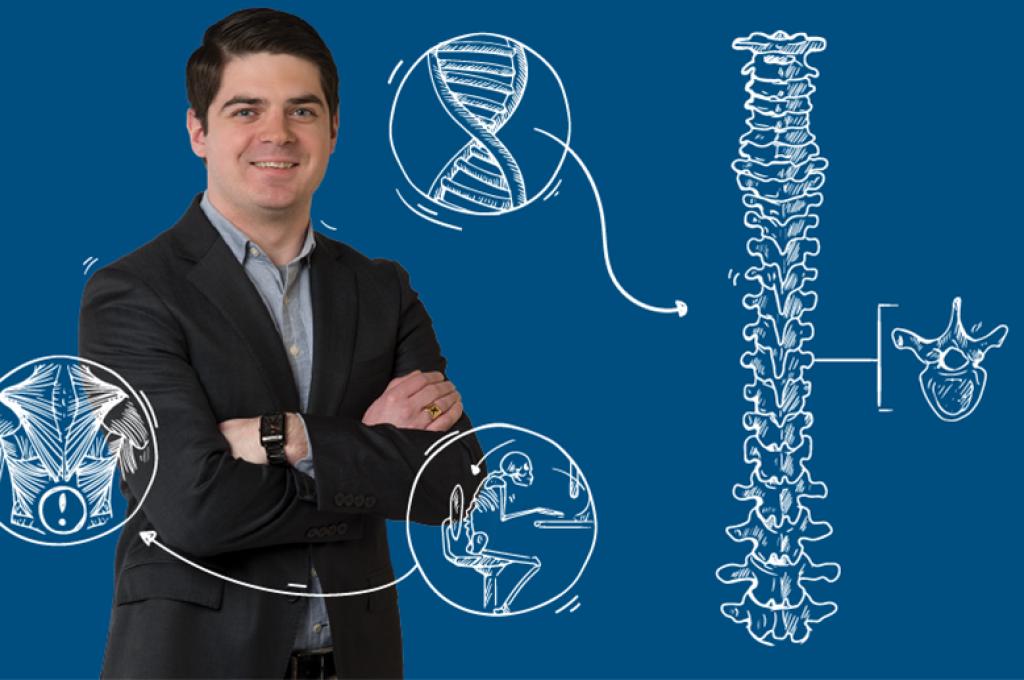

Ryan Greene was writing a literature review when the subject of his research hit him with physical force.

He’d just risen from his desk chair when his back muscles seized up and he doubled over in agony.

“It hurt really bad. I thought I’d have to go to the hospital,” he says.

The subject of the paper he was typing? The effects of prolonged sitting on back pain.

Greene is a Master’s student in clinical epidemiology at Memorial University of Newfoundland. Working under Diana De Carvalho, Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation Professor in Biomechanics, he studies how sitting affects the human spine.

It’s a field of research that’s still in its infancy; researchers don’t yet know if, or how, prolonged sitting leads to back injuries. But with studies showing that 70 to 85 percent of people will experience low back injury at some point in their lives — and people spending increasing amounts of time sitting in front of computer screens — the correlation is intriguing. And the research conducted in De Carvalho’s lab could have practical applications for millions of Canadians.

“There’s no occupational standards right now around sitting,” says De Carvalho, a chiropractor with a PhD in kinesiology, who serves as assistant professor in Memorial’s Faculty of Medicine, cross-appointed to the School of Human Kinetics and Recreation.

“We need good quality evidence to start driving recommendations on things like: sitting times, when people should be taking breaks, and what they should be doing. Is there a chair type that might be helpful? Or sit/stand desks? We have a responsibility to provide safe workplaces for employees.”

Though he’s passionate about scientific research, Greene’s path to a Master’s degree wasn’t straight.

He grew up in Blue Mountain, a rural community two hours outside of Halifax. Being surrounded by nature spurred his interest in biology — an interest that continued to grow through his high school years, as he discovered a love of genetics and microbiology.

“You can put a question out there and see the world through a different lens, and understand yourself in a different way,” he says.

He entered an undergraduate science program at St. Francis Xavier University, but didn’t find his footing until his final two years. He then decided to go back to school for a business degree.

“I thought I could do healthcare management. I thought business and science would be a good background for that.”

To finance his business degree, he ran the labs at an oyster hatchery in New Brunswick. After two years, water-borne pathogens swept up the Northumberland Strait and wiped out the hatchery, but the experience made him rediscover his love of science.

He applied for an MSc in clinical epidemiology at Memorial and made the move to St. John’s, N.L.

“The biggest thing I found with my undergrad was that it left me hungry for more,” he says. “I thought, I need to go back to what I really like … where I could study lots of interesting things and do something that is beneficial to people.”

Combining fundamental science with practical applications, De Carvalho’s “Spine Lab” focuses on injury mechanisms, treatment options and prevention strategies. She started the lab in 2015 and then was able to expand her resources using CFI funding in 2016 to purchase an array of equipment including motion-capture cameras, wireless electromyography gear and force plates, which allow her and her students to study in detail how the muscles and joints of the back respond to different stresses.

“Ryan’s fantastic. He’s very self-motivated,” she says. “I’ve given him one of the more challenging areas of my research program.”

Greene’s thesis experiment examines whether prolonged sitting leads to a slower reflex time in the muscles of the back. He hypothesizes that the inactivity of sitting may cause muscles to react more slowly when they are suddenly called into action — for example, to swivel around or pick up an object.

As well, sitting strains the muscles of the back, which causes them to become stretched over time — a phenomenon known as “tissue creep.” Greene’s experiment seeks to determine whether this tissue creep occurs when people sit in office chairs, resulting in increased ranges of spine motion: essentially creating a situation where a worker could bend or twist too far, placing spine joints at risk of injury.

This extra range of motion may also cause changes in how back muscles normally respond to challenges. For example, a delay in reaction time may impair the muscles’ ability to stabilize the spine, resulting in back injury, he hypothesizes.

“The classic example is a delivery worker,” says Greene. “They’re sitting at a computer or in a van, and then they get up to lift a heavy parcel, and they throw their back out.”

Greene says he’s not sure where his research will take him after he finishes his Master’s degree but for now he’s happy to be working in a field that can directly affect people’s lives.

“It’s hard to leave something like this when it’s such a hot topic, and there’s so few answers,” he says. “There’s recommendations, but there’s no concrete, definitive answers for back pain in office environments.”