Ajay Heble remembers the time he saw more than half a dozen jazz musicians from six different countries get together and jam, despite having no common language. “They just started to play, and what they did was absolutely amazing,” he recalls. “There’s a lesson to be learned there.”

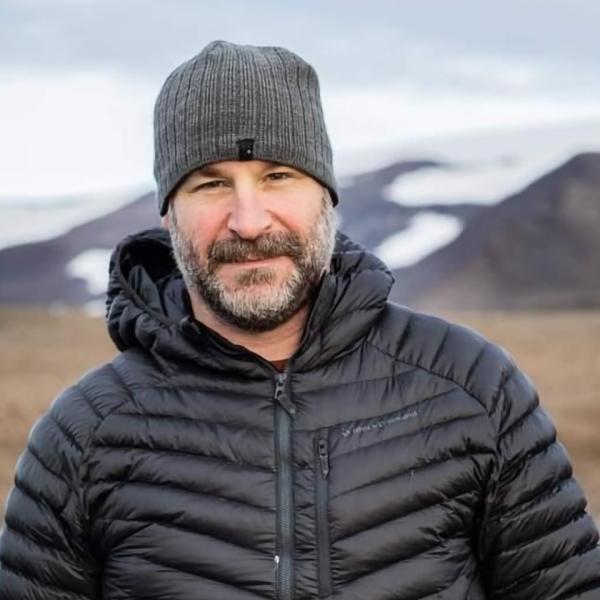

Today, Heble is applying that lesson as the director of the International Institute for Critical Studies in Improvisation (IICSI), centred at the University of Guelph. For 15 years, Heble and his team have explored how the principles of improvisation can contribute to collaboration, adaptation, trust and risk-taking in an ever-more globalized world. In the process, it has established an entirely new field of inquiry.

Along with musicians, IICSI boasts a team that includes a surgeon, lawyers, historians, sociologists, philosophers and more, as well as 40 community partners around the world. “This really is a collaborative project,” says Heble.

Over the years, the group has conducted research, hosted workshops and conferences, published a peer-reviewed journal and organized performances. However, a lack of dedicated performance space has made programming a challenge.

That’s about to change. With funding from CFI, work is underway on ImprovLab: a world-class facility, designed by the award-winning Diamond Schmitt Architects.

When completed, it will feature a 300-seat research and performance space, top-of-the-line AV equipment to document workshops and research studies, and telematic technology to enable live performances with participants in other parts of the world.

The new capabilities of ImprovLab will allow researchers to closely monitor and document “the moments and interactions that build to create impact,” says Heble. So far, his research group has relied on camera footage for this kind of observation, but being able to hone in on individuals, consistently and across a long time period, means they can track minute shifts in expression, posture and musical practice.

“This kind of data will help us understand the subtleties of these interactions and to hone programming to better meet our team’s and our collaborators’ goals,” he says. “There’s a lot of excitement around this project. This is really going to help advance our research.”