The soaring rise in the cost of living and the lack of affordable housing is raising the spectre of more widespread poverty in Canada and around the world. About 2.4 million Canadians live below the poverty line, with persons with disabilities, children, Indigenous people and recent immigrants being disproportionately affected. Since 2019, the number of visits to food banks across the country has increased by an average of more than 20 percent, while some have recently seen spikes of over 50 percent.

But what does it really mean to live in poverty? “Despite its prevalence,” points out Stephen Wright, a professor of social psychology at Simon Fraser University (SFU) in Burnaby, B.C., “poverty remains largely misunderstood.” And largely stigmatized, with many believing it is synonymous with homelessness and drug use, or that people living in poverty are mainly responsible for their fate. The reality, however, is far more wide-ranging and complex.

Understanding the psychological underpinnings of our perceptions of poverty is at the core of experiential research conducted at SFU’s Intergroup Relations and Social Justice Lab, directed by Wright. Funded in part by the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the lab has been running poverty simulations since 2016, which aim to give participants a taste of living day to day with limited means. Ultimately, the goal is to reduce stigma surrounding poverty.

On pause since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the simulations are set to start up again in early 2023, a timely relaunch given the current economic climate.

A month of scraping by

Called “Making Ends Meet,” the simulations evolved from a classroom exercise for a course on intergroup relations to a full-blown research project when Wright noticed a common bias in his students’ views of poverty. “One of the things that struck me about that class was how the stereotypes about homeless people, about people living in poverty, were really quite narrow,” says Wright. “I was quite concerned that we had left this out of our public education: how we should think about people who are economically disadvantaged.”

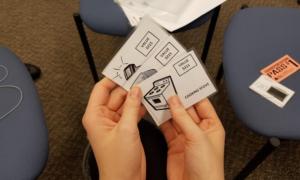

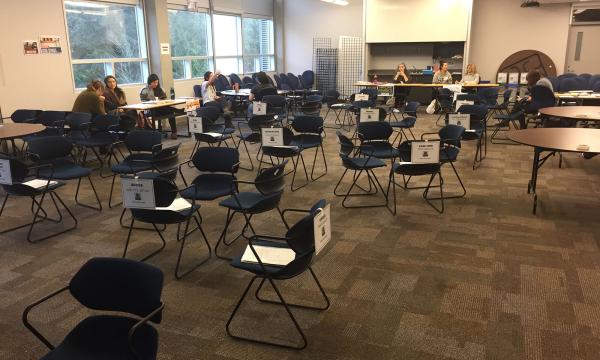

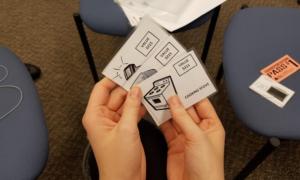

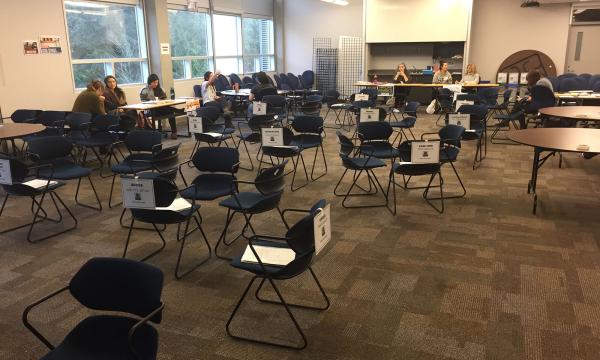

Adapted from a poverty simulation developed by the Missouri Community Action Network, Making Ends Meet is a three-hour learning intervention during which participants take on the role of an individual or a member of a low-income family grappling with managing daily life over the course of a month.

About 25 student volunteers act as providers working in services such as a bank, a grocery store, a daycare, a medical clinic, and employment and social services offices. Each participant is faced with a unique set of challenges, be it single parenthood, physical or mental disabilities or unemployment.

At the end of the simulation, participants fill out a questionnaire about their experience and discuss it and its relevance to the real world with the group during a debriefing session.

“What we find is that it’s extraordinarily effective,” explains Wright. “People get extremely worried, they’re very involved in it. They get angry, they get frustrated, they get sad. Some people give up. We’re not implying to anyone that this is a real experience, but we’re giving them a glimpse of the difficulty of trying to manage our world with inadequate funds, and what it feels like to have to go and ask for help.”

So far, about 800 people have participated in the simulations, including students and other groups at SFU, as well as elementary and high-school teachers in Burnaby, B.C. There are plans to offer the intervention to other community organizations, too.

From empathy to action to address Canadian poverty

Wright’s research has revealed that the simulations have a positive effect on participants’ attitudes toward the economically disadvantaged, an important step toward reducing stigma and discrimination surrounding poverty.

“We get really interesting data about how people move from their initial positions to positions that include more empathy and a different response to what it means to be poor,” he says. “We can show that it makes people more likely to support housing policies, wealth distribution policies, and so on.” Participants in the simulations have even been moved to get involved in community projects or to take political action to support those living in poverty.

Maitland Waddell, a PhD candidate in social psychology at SFU, was introduced to the poverty simulation as an undergrad in Wright’s course on intergroup relations. The experience motivated him to get involved in the Intergroup Relations and Social Justice Lab, where he continues to contribute as a Making Ends Meet facilitator.

Waddell would like to further hone the simulation by tapping into the knowledge of people with lived experience of poverty. “The original intention of the simulation was to provide a more nuanced, more diverse representation of what poverty looks like,” he says, “As the price of gas goes up, as groceries increase in cost, I think there’s a great opportunity right now to start a conversation about the systemic causes of poverty, about things we have no control over that nevertheless drive us into poverty. This (research) work could act as one avenue to start these discussions.”

By extending the research beyond the lab into the community, the hope is that Making Ends Meet could help carve a path to meaningful social change for some of the country’s most vulnerable.